(2020)

Over the last few years I’ve seen two prevalent points of view regarding the word “enby”. Some people consider it a necessary noun without age connotations, simply a phonetic spelling of the abbreviation of the adjective nonbinary, NB, and refer to nonbinary people collectively as enbies. On the other hand, I can’t count how many times I’ve seen someone tweet something like, “please stop referring to us all as enbies, not all of us are comfortable being referred to like that!” When asked for further thoughts on this issue, people often describe finding it condescending or infantilising.

I originally discovered the term (as part of “enbyfriend”) on Tumblr, in a post inspired by creator @revolutionator. Their original post is no longer accessible, but after some digging I found that it was posted sometime no later than 2013, seven years ago at the time of writing.

[Edit 2023-04-17: The original post is still up! The URL is currently https://02348294832908091.tumblr.com/post/60853952929 and you can’t view it (or archive it on the Wayback Machine or similar) without a Tumblr account, but I’ve saved it as a PDF, which you can view here. It was coined on 10th September 2013.]

i wish there was an nb equivalent to words like boys and girls

nb

enby

enbies

It seems pretty clear that the word enby was originally intended as a noun to complement boy and girl, specifically to refer to nonbinary minors – but my experience was that not everyone uses it that way or is aware of the word’s origins.

I am not into the idea of imposing a meaning on a word. I prefer the “common usage” approach, of using spellings and definitions that are most widely accepted and understood. Thankfully, this year I asked participants for their approximate ages, and the word enby was in the checkbox identity list for its fourth year, which means I can find out the ages of the people claiming that word for themselves.

In other words, it’s possible for me to find out whether enby tends to be used more frequently by younger people, similarly to boy and girl. I think most people can imagine that it would be inappropriate in many contexts to address a room full of adult women of various ages with “hello, girls,” so finding out how nonbinary people might feel about this kind of situation with a sample size of 24,000 is very valuable. (The usual caveat, though – most Gender Census participants are from the USA, and these linguistic conventions vary from culture to culture.)

I started out by counting how many participants identified as either “boy” or “man”, and I called this group, for want of a better word, “male”. I calculated what percentage of that group identified each as “boy” and “man”, since many identified as both. I then did the same for “girl” and “woman”, grouped as “female”. Boy, man, girl and woman were all checkbox options in the identity question.

The conditional formatting gives a rough visual guide of how popular a term is in an age group: the darker the shade, the higher the percentage. To walk you through how this table works with an example, in the first section of the first row, 15.3% of participants aged 11-15 identified as either boy or man, and of that 15.3%, 89.3% identified as boy and 49.9% identified as man.

There is a line across the whole table after 51-55 because over age 55 the sample sizes start to get a lot smaller and might be unreliable.

Interesting but irrelevant: We can see that as the ages of participants increased, participants were less likely to identify with “male” words, and more likely to identify with “female” words – not something I could have predicted, but a clear and fascinating trend.

More relevant: Within those subsections, and in both subsections, as the ages of participants increased, participants were less likely to identify with the “child” words and more likely to identify with the “adult” words. This is the useful part. We don’t have a group of cisgender people to use as a control group, but I think it’s not unreasonable to expect nonbinary people’s claiming of those words to reflect society’s use of them in general. (Most people can agree that most of the time, in most contexts, the word “boy” is used to describe a child who is male.) What this means is we can use these trends for comparison with use of the word “enby”. (However, we can’t prove causation with correlation yet. More on that later.)

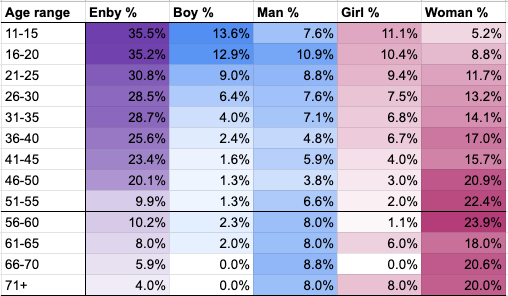

I made a new table for more comparison, using the number of participants who identified as enby, boy, man, girl and woman as a percentage of total participants in each age group.

Again, the higher percentages are filled with a darker colour to make patterns easier to spot. Starting at the top left, 35.5% of all participants aged 11-15 identified as enbies, 13.6% of all participants aged 11-15 identified as boys, etc.

At younger ages, people are more likely to call themselves “enby” compared to “boy” or “girl”, which makes sense when you consider the target group for the survey: “anyone whose genders (or lack thereof) aren’t described by the M/F binary.” And the “dark-to-light” pattern of “boy” and “girl”, being used less often as age of participants increased, is reflected in the use of “enby”.

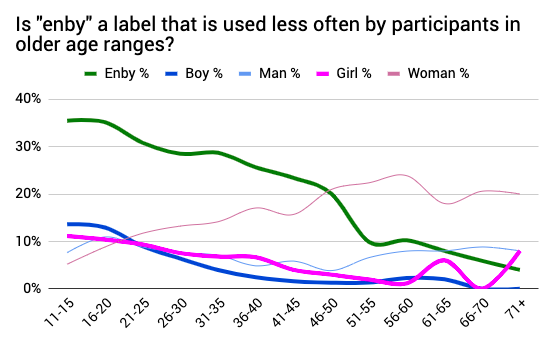

I turned it into a graph to get a different perspective:

The bold lines are the “minor” words, and the finer lines are the “adult” words. You can see how “enby” (dark green) follows that downward trend as age increases. (Note again that sample sizes in age ranges over 55 are too small to be reliable.)

Since there is a steady decrease in all three terms as age increases, we can look at whether use of the term “enby” decreases at a similar rate. Use of “boy” starts at 13.6% for the 11-15 age range, and halves by 26-30, a comparatively steep drop. “Girl” starts at 11.1% and halves by 41-45, which is much older, and it matches my experience (with exceptions) of women being commonly referred to as girls and also being more comfortable with that. Use of “enby” starts at 35.5% and halves by 51-55. This suggests that claiming the word “enby” feels more okay to older people. If I were a speculating kind of person (and I definitely am), I might wonder if the impression of “enby” as a diminuitive word doesn’t have as strong a foothold, and perhaps that’s because the term is relatively new?

I will have to ask about the word “enby” while also asking for participants’ ages for many years before I can conclude definitively that “enby” is generally a word referring to nonbinary children. It’s possible, for example, that older participants hadn’t come across enby in the first place. We can’t be sure that people tend to become less comfortable with the word “enby” as they age unless we follow its use as those people age. It’s possible that “enby” will go out of fashion before we can get any reliable long-term data.

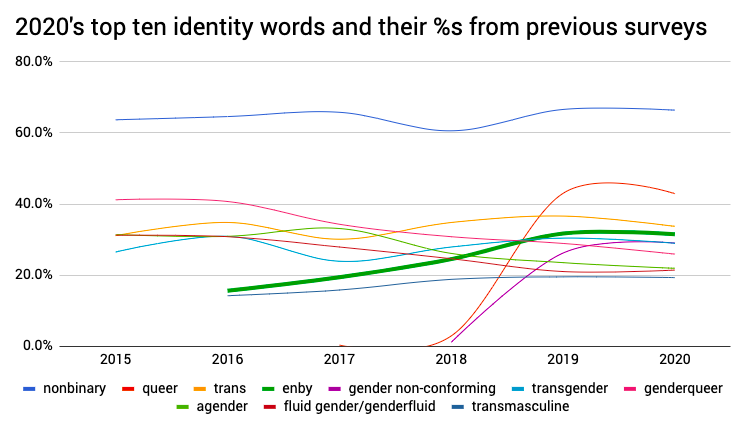

And it is worth noting that in its most popular age group (11-15), enby was only claimed by 35.5% of participants. Overall, that figure drops to 31.5%. Here’s how it fits in:

- nonbinary – 66.4%

- queer (partially or completely in relation to gender) – 42.9%

- trans – 33.7%

- enby – 31.5%

- gender non-conforming – 29.0%

My overall conclusion here is that while “enby” doesn’t have such strong age connotations as “boy” or “girl”, for whatever reason older participants did tend to feel less comfortable being addressed that way, and under a third of participants are happy to be described as an enby. I would especially recommend avoiding referring to groups of nonbinary people as enbies if you want to include people of all ages.

That does take us to the next question: do we need a noun for nonbinary adults? (A man, a woman, a… nonbinary?)

You can see the spreadsheet of results here.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed it and would like to give something back, you could increase your chances of taking part in future surveys by following on Tumblr, Twitter or the Fediverse, or subscribing to the mailing list. Alternatively, you could take a look at my Amazon wishlist.

2020-06-15

email: hello@gendercensus.com